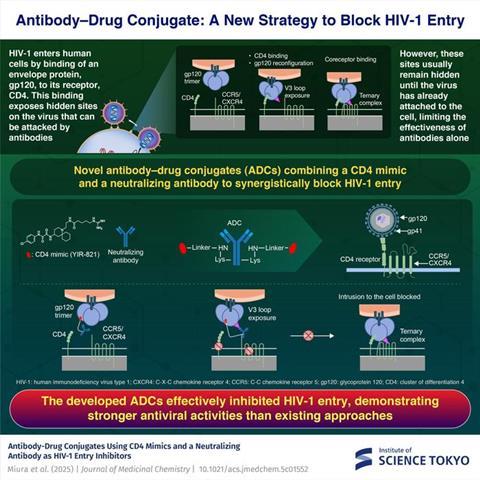

New antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) developed at Institute of Science Tokyo combine a CD4 mimic with neutralizing antibodies for enhanced suppression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

By targeting the gp120 on the viral envelope via a two-step mechanism, the ADCs effectively block viral entry—offering seven times better efficacy than existing approaches. Overall, the findings point towards a promising new direction for HIV treatment—targeting two viral sites with a single molecule.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains a major global threat to health, affecting millions of people worldwide. Despite decades of research, current clinical approaches, such as combination antiretroviral therapy, still face challenges, such as drug resistance, side effects, and high costs. One promising approach is to block HIV before it enters the host cell. However, when used alone, these drugs and antibodies often show limited potency.

Unique strategy

Building on this, a team of researchers from Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo), Japan, developed a novel antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) that uses a unique strategy to block HIV entry.

The study was led by Professor Hirokazu Tamamura, along with researcher Yutaro Miura from the Laboratory for Biomaterials and Bioengineering, Institute of Integrated Research, Science Tokyo, together with Specially Appointed Professor Shuzo Matsushita from the Chemo-Sero-Therapeutic Research Institute for Anti-Viral Agents and Hematological Diseases, Joint Research Center for Human Retrovirus Infection, Kumamoto University, Japan. The study was made available online on December 15, 2025, and was published in Volume 68, Issue 24 of the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry on December 25, 2025.

Hidden sites

“HIV-1 virus enters human cells when its envelope protein gp120 binds to the receptor protein, CD4, exposing hidden sites in gp120 that antibodies can attack,” explains Prof. Tamamura. “However, these sites are revealed after attachment to CD4, limiting the effectiveness of antibodies alone.”

Targeting this process, the researchers combined a CD4 mimic (a small molecule designed to imitate CD4) with a neutralizing antibody that recognizes the hidden sites on HIV. When the CD4 mimic binds to gp120, it induces structural changes in the viral protein and just like CD4, it exposes regions that the neutralizing antibody can then recognize and bind to more effectively. By chemically linking these two components into a single molecule, the researchers ensured that both components act on the same virus particle at the same time.

“By combining the CD4 mimic directly with the neutralizing antibody, we aimed to amplify the antibody’s antiviral activity while maintaining its specificity,” comments Miura.

HIgher anti-HIV activity

Further experiments revealed that the developed ADC demonstrated substantially higher anti-HIV activity than the CD4 mimic alone or the antibody alone. In optimized designs, the ADC enhanced antiviral potency by several-fold compared to the parent antibodies. Notably, the ADCs retained their selectivity for HIV, highlighting that increased activity did not come at the expense of safety.

READ MORE: New antibody breakthrough offers hope against evolving SARS-CoV-2 variants

READ MORE: Reactivation compound could be latest weapon against HIV

Apart from the improved potency, the ADC strategy might reduce adverse effects as the ADC only acts on the viral particles rather than the host cells. This offers a more targeted therapeutic profile, making the antibody-based HIV treatment a gentler alternative to current drug regimens. With further refinements, the researchers believe the ADC could lead to even more powerful HIV entry inhibitors. “In the future, these molecules may form the basis of a new therapeutic strategy aimed not only at controlling HIV infection but also at its eradication,” remarks Tamamura.

Overall, this study opens new possibilities for antiviral drug development. It shows how rational molecular design can unite small molecules to address persistent infectious diseases—in an innovative and clinically relevant manner.

Topics

- antibody–drug conjugates

- Antimicrobials

- Asia & Oceania

- CD4 mimic

- Clinical & Diagnostics

- gp120

- Hirokazu Tamamura

- Immunology

- Infection Prevention & Control

- Infectious Disease

- Institute of Science Tokyo

- Kumamoto University

- Medical Microbiology

- neutralizing antibodies

- One Health

- Pharmaceutical Microbiology

- Research News

- Shuzo Matsushita

- Viruses

- Yutaro Miura

No comments yet