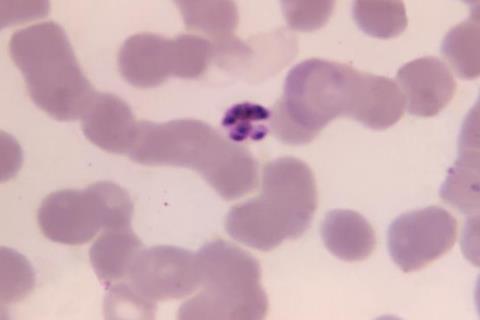

Genetic diversity of the malaria parasite in pregnant women and children declined in an area targeted for malaria elimination in Mozambique, according to a study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal), a centre supported by “la Caixa” Foundation and the Manhiça Health Research Centre (CISM).

The findings, published in Nature Communications, highlight the added value of routine sampling of pregnant women as a cost-effective strategy to enhance genomic surveillance of the parasite and detect changes in transmission within the community.

Genomic surveillance of the malaria parasite P. falciparum is essential to monitor the emergence and spread of drug-resistant parasites. But it can provide much more information. “We believe that the genomic diversity of the parasite population can also help us evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at eliminating the disease: we expect lower genetic diversity of the parasite in areas with less transmission,” says ISGlobal researcher Alfredo Mayor.

Sentinel population

Regular collection of samples for genomic surveillance is challenging and costly, particularly in low-resource settings; but Mayor and his team have a solution: pregnant women attending their first antenatal care visit as an easy-to-reach sentinel population. The team previously showed that the malaria burden in pregnant women mirrors that of the community. In this study, they evaluated whether the genetic diversity of the parasite in pregnant women is also representative, and whether it can inform about changes in transmission levels.

The research team sequenced P. falciparum sampled from 289 women attending their first antenatal visit and 93 children from the community, aged 2-10 years old. The samples were collected between 2015 and 2018 in three areas of southern Mozambique: one with high-transmission of the disease (Ilha Josina) and two with low-transmission (Magude, where elimination interventions were implemented, and Manhiça).

Impact of interventions

The analysis confirmed that genetic diversity and the prevalence of drug resistance markers were consistent between women attending antenatal care and children from the community. The parasite population in Ilha Josina had the highest genetic diversity, while Magude had the lowest. Furthermore, in Magude there was a clear decline in the diversity of parasites infecting a single individual (intra-host diversity), indicating a reduction in the size of the parasite population following the elimination interventions. No decrease in intra-host diversity was observed in Manhiça.

“Our findings reveal the impact of interventions on the structure of the parasite population, which is not as apparent when looking only at the number of cases during the same time period,” says Nanna Brokhattingen, first co-author of the study.

“Parasite surveillance in pregnant women can complement clinical and epidemiological data when evaluating the impact of malaria control and elimination interventions,” adds Mayor.

The authors conclude that routine genomic surveillance at antenatal care clinics represents a cost-effective and convenient approach to inform about changes in disease transmission.

No comments yet