Researchers from King’s College London have called for urgent changes to the way new antibiotics are developed to address the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

In a new review published in npj Antimicrobials and Resistance, the authors outline the scientific, economic, and regulatory barriers that are slowing progress in the fight against highly resistant bacterial infections.

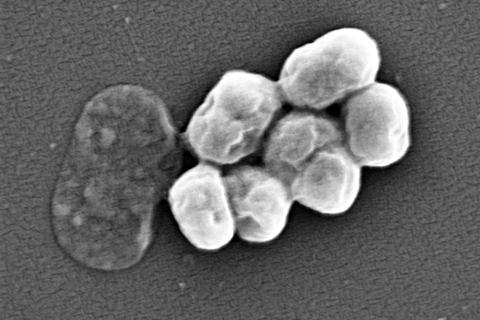

AMR is a growing global health crisis, already linked to nearly 5 million deaths each year. Without effective action, this number could rise to 10 million annually by 2050. Some of the most concerning threats come from Gram-negative bacteria. These include the bacteria Klebsiella pneumoniae, which can cause deadly bloodstream infections from simple medical procedures in hospitals, and Acinetobacter baumannii, which can lead to ventilator-associated pneumonia.

READ MORE: Efflux pumps conferring antibiotic resistance found in archaea for the first time

READ MORE: Climate, conflict, and antimicrobial resistance: unravelling the threat to global health

Despite this, very few new antibiotics have reached the market in the past two decades. The need is clear, but the development process remains extremely difficult.

Ecnomic challenge

One major challenge is economic. Antibiotics are usually used for short periods and are often used only when necessary to slow the development of resistance. This means they generate much less revenue than drugs for chronic diseases like cancer, which are used over longer timeframes and are more profitable. As a result, many of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, such as AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer, have withdrawn from antibiotic research.

The authors argue that new models are needed to make antibiotic development more attractive to industry. They highlight the importance of separating profits from the volume of antibiotics sold. A mix of incentives could help: push incentives like research grants and tax breaks to support early-stage research, and pull incentives like market entry rewards or subscription payments to support successful products.

The review highlights the UK’s Antimicrobial Product Subscription Model as a positive example. Launched in 2022, it pays companies a fixed annual fee for access to new antibiotics, regardless of how much is used. The proposed PASTEUR Act in the US follows a similar approach.

Regulatory hurdles

Regulatory hurdles are another key barrier. Clinical trials for antibiotics are often large, complex, and expensive, with difficulties in recruiting suitable patients. Different standards across countries also make the process more complicated. The authors call for better global coordination and clearer guidance on trial design and evaluation, to make approval processes more efficient and predictable.

There are several scientific challenges in developing new antibiotics for Gram-negative bacteria. These include overcoming their tough, protective outer membrane, which prevents many drugs from entering. Additionally, these bacteria have resistance mechanisms such as efflux pumps that expel antibiotics and enzymes that break them down. Another major challenge is identifying new drug targets and effective compounds capable of killing these highly resistant organisms.

Combining expertise

The review emphasises the need to combine different areas of expertise to revitalise antibiotic discovery. New scientific approaches include using artificial intelligence to identify promising molecules, exploring under-studied environments such as the deep sea, and examining rare microbiomes. Non-traditional approaches such as phage therapy are also being explored, though they bring their own challenges.

Lead author, Miraz Rahman, Professor of Medicinal Chemistry and Antimicrobial Research Theme Group Lead at King’s College London, said: “Reviving the antibiotic pipeline will require cooperation across academia, industry, policy, and global health systems. We need not only innovative science but also a supportive economic and regulatory environment to bring new antibiotics to patients.”

The review is a call to action to scientists, drug developers, governments, and all other stakeholders with influence over the antibiotic development pipeline. It describes the present challenging landscape and presents a practical path forward that urges stakeholders to work together to safeguard the future of modern medicine.

No comments yet