Researchers at the University of California San Diego have discovered a promising new treatment approach for pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest and most treatment-resistant forms of cancer. The approach leverages the body’s natural immune response to cytomegalovirus (CMV), a common but typically harmless virus that most people are infected with at some point in their lives.

By working with CMV experts from La Jolla Institute of Immunology (LJI), the team was able to harness CMV immunity to significantly delay pancreatic tumor growth and extend survival in mice. The results, published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer, offer a simple, highly-accessible treatment possibility for pancreatic cancer and other difficult-to-treat solid tumors.

“We were thrilled to see such a strong response in our preclinical studies, by delivering small pieces of viral proteins — CMV peptides — to pancreatic tumors, we were able to redirect the virus-specific T cells against the cancer cells,” said co-senior author Hurtado de Mendoza, PhD, assistant professor of surgery at UC San Diego School of Medicine.

“Because our strategy relies only on previous immunity against CMV and not on the specific characteristics of an individual’s tumor it has the potential to be an off-the-shelf solution that could be applicable to a large number of patients.”

Difficult to treat

Pancreatic cancer accounts for 3.3% of all cancer cases in the United States, but it accounts for 8.4% of deaths. This higher proportion of cancer deaths is in part because pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to treat, with a five-year survival rate of just 12%. Current immunotherapies that are successful in melanoma or lung cancer patients have mostly failed in pancreatic cancer, leaving patients with few options.

“Some tumors have plenty of mutations, and all of those mutations make these tumors easy for the immune system to see and target,” said co-first author Remi Marrocco, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at LJI. “Pancreatic cancer has fewer mutations and a lot of immunosuppressive cells that inhibit immune responses against the tumor. It’s a ‘cold’ tumor.”

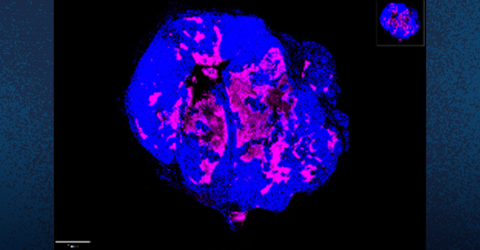

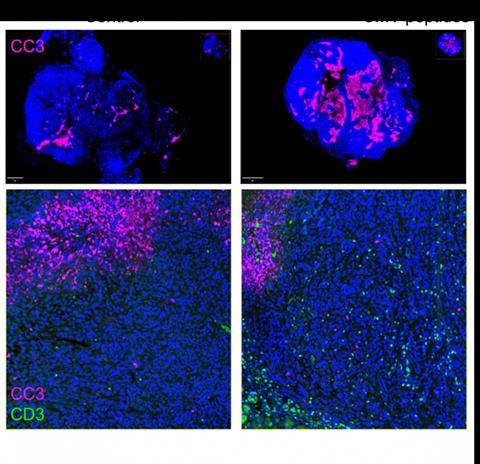

The new approach works by injecting CMV-derived peptides — small protein-like particles — directly into the bloodstream. This activates and mobilizes immune cells, called memory T cells, that recognize the CMV peptides from a previous infection. When these peptides are present in the tumor, CMV-specific T cells can infiltrate and kill the tumor cells.

“There are more memory T cells that recognize CMV, than probably recognize any other known virus or bacteria at this point,” said co-senior author Christopher Benedict, PhD, associate professor at LJI. These cells make up literally 10% or more of our memory T cells, which is a huge number.”

The findings

When testing their approach in mice with a previous CMV infection, the researchers found:

- Mice treated with CMV peptides experienced significantly delayed tumor growth.

- Treated mice survived 42 days compared to 25 days for control mice, a 70% increase in survival.

- The therapy was effective at a well-tolerated dose, with minimal toxicity observed.

- Though the treatment was given by a systemic injection, CMV memory T cells preferentially recognized and targeted the tumors during treatment with no damage to other organs.

- The treatment changed the gene expression profile of tumor cells, making them more sensitive to an immune response.

“This therapy represents a significant step forward in the fight against pancreatic cancer, and we’re hopeful that it could provide new treatment options for patients with limited alternatives,” added co-first author Jay Patel, a research assistant at UC San Diego. “CMV-specific T cells have the potential to become a powerful tool in the fight against cancer, and we’re only just beginning to unlock their possibilities.

Challenging cancers

The researchers are also exploring the potential of their approach to treat other challenging cancers, including triple-negative breast cancer, for which Benedict and Hurtado de Mendoza recently received a Curebound Discovery Award. In order to bring this therapy one step closer to the clinic, they are now working with humanized mouse models using a patient’s tumor and blood to provide CMV immunity. They are also characterizing a pool of human CMV peptides discovered by the Benedict and Sette labs at LJI, making it possible to find the best match for each patient based on an individual’s genetics.

READ MORE: Cytomegalovirus breakthrough could lead to new treatments

READ MORE: Scientists discover novel immune ‘traffic controller’ hijacked by virus

“This approach has the potential to be tumor-agnostic, meaning it could be effective against a range of cancer types, including breast cancer, lung cancer, and others,” said. Hurtado de Mendoza. “We’re excited to explore its potential in humanized mouse models to bring it one step closer to clinical trials.”

Additional coauthors on the study include: Rithika Medari, Philip Salu, Alexei Martsinkovskiy, Siming Sun, Kevin Gulay, Malak Jaljuli, Evangeline Mose, Andrew Lowy at UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center and Eduardo Lucero-Meza, Catarina Maia and Simon Brunel at the La Jolla Institute.

The study was funded, in part, by grants from Foundation for a Better World and the National Institutes of Health (R21CA286198, AI139749, AI101423).

Topics

- Cancer Microbiology

- Christopher Benedict

- CMV-derived peptides

- cytomegalovirus

- Disease Treatment & Prevention

- Hurtado de Mendoza

- Immunology

- Innovation News

- Jay Patel

- La Jolla Institute of Immunology

- One Health

- pancreatic cancer

- Pharmaceutical Microbiology

- Remi Marrocco

- University of California San Diego

- USA & Canada

- Viruses

- Young Innovators

No comments yet