To treat bacterial infections, medical professionals prescribe antibiotics. But not all active medicine gets used up by the body. Some of it ends up in wastewater, where antimicrobial-resistant bacteria can develop. Now, to make a more efficient antibiotic treatment, researchers reporting in ACS Central Science have modified penicillin so that it’s activated only by green light. In early tests, the approach precisely controlled bacterial growth and improved survival outcomes for infected insects.

“Controlling drug activity with light will allow precise and safe treatment of localized infections,” says Wiktor Szymanski, a corresponding author of the study. “Moreover, the fact that light comes in different colors gives us the ability to take the spatial control of drug activity to the next level.”

READ MORE: Coumarin glycosides reverse enterococci-facilitated enteric infections

READ MORE: Researchers develop new approaches in the fight against drug resistance in malaria

Scientists can add a light-sensitive molecule to drug compounds to keep them inactive in the body until they’re needed. When light shines on a modified compound, the extra molecule breaks away and then releases the active drug. This process gives scientists precise control over when and where drugs are activated.

Previous light-reactive tags, such as coumarin added to the opioid reversal agent naloxone, require high-energy UV or blue light to kick-start the process. But molecular tags made from other coumarin compounds can be released by green light, a less intense form of light. So, Albert Schulte and Jorrit Schoenmakers, along with their supervisors and colleagues, wanted to develop coumarin-based modifications to create light-activated antibiotics.

Coumarin-based molecule

The researchers first linked a coumarin-based molecule to the portion of penicillin that targets bacterial cell walls, making the antibiotic inert. When exposed to green light, the new molecule broke away, activating the penicillin.

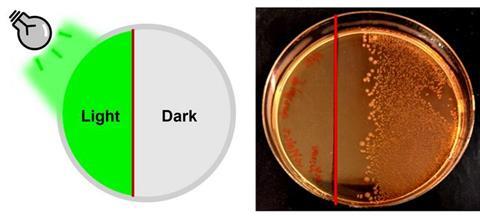

Initial experiments with bacteria grown in petri dishes showed that exposing the modified penicillin to green light significantly inhibited E. coli colony formation and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm development.

Next, the researchers treated Staphylococcus aureus-infected wax moth larvae, which have immune defenses similar to those of humans, with an injection of the modified penicillin followed by green light therapy. Treated larvae had an improved survival rate (60%) compared to infected larvae that were left alone (30%). These observations show a successful proof of concept in living organisms, say the researchers.

Promising results

The researchers add that these results are promising for future work that may expand the system to multiple light beams and different colors of light for controlling antibiotic activity in larger living organisms, including humans.

The authors acknowledge funding from an ERC Advanced Investigator Grant, the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science of The Netherlands Gravitation Program, and the Graduate School of Medical Sciences of the University of Groningen.

Topics

- Albert Schulte

- Antibiotics

- Bacteria

- Biofilms

- coumarin

- Escherichia coli

- green light therapy

- Infection Prevention & Control

- Jorrit Schoenmakers

- light-activation

- One Health

- penicillin

- Pharmaceutical Microbiology

- Research News

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Staphylococcus epidermidis

- UK & Rest of Europe

- University of Groningen

- Waste Management

- Wastewater & Sanitation

- Wiktor Szymanski

No comments yet