A toxin-secreting gut bacterium may fuel ulcerative colitis by killing protective immune cells that maintain intestinal homeostasis, according to a new study. The findings suggest potential for new treatment strategies.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease affecting millions of people worldwide in which the body’s immune system attacks the digestive tract, often causing severe and recurring symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and intestinal bleeding.

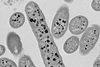

Although the underlying causes of UC remain unclear, previous research indicates that failure of the intestinal epithelial barrier plays an important role in disease progression. Intestinal macrophages are crucial to maintaining the gut’s protective epithelial barrier.

Zhihui Jiang and colleagues examined colon biopsies from patients with UC and found that subepithelial, tissue-resident macrophages were almost completely absent, even in areas that were not yet showing inflammation. Further experiments in mouse models confirmed that removing these macrophages made the colon highly vulnerable to inflammation.

Microbial cause

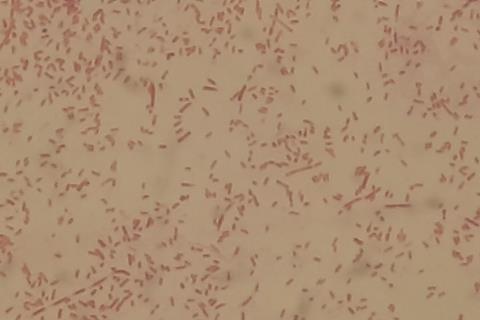

Suspecting a microbial cause, Jiang et al. discovered that fecal samples from UC patients contained aerolysin, a pore-forming toxin produced by a variant of Aeromonas bacteria, which proved selectively lethal to macrophages but not to epithelial cells.

In mouse models, infection with this macrophage-toxic bacterium (MTB) sharply worsened colitis, whereas mutant strains lacking aerolysin did not. What’s more, MTB infection had no effect in mice already depleted of gut-resident macrophages, and neutralizing aerolysin with antibodies alleviated disease symptoms.

In a clinical survey involving 574 participants, Jiang et al. discovered that Aeromonas species were present in 72% of UC patients but only ~12% of healthy individuals and nearly absent in those with Crohn’s disease, further linking the bacterium to disease occurrence.

“Directly targeting these microbes and their toxins could be a promising avenue for treating [inflammatory bowel disease] without inhibiting the patients’ immune system with biologics, such as antibodies, and steroid drugs,” write Sonia Modilevsky and Shai Bel in a related Perspective.

No comments yet