Bacteriophages have been used therapeutically to treat infectious bacterial diseases for over a century. As antibiotic-resistant infections increasingly threaten public health, interest in bacteriophages as therapeutics has seen a resurgence. However, the field remains largely limited to naturally occurring strains, as laborious strain engineering techniques have limited the pace of discovery and the creation of tailored therapeutic strains.

Now, researchers from New England Biolabs (NEB®) and Yale University describe the first fully synthetic bacteriophage engineering system for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an antibiotic-resistant bacterium of global concern, in a new PNAS study. The system is enabled by NEB’s High-Complexity Golden Gate Assembly (HC-GGA) platform.

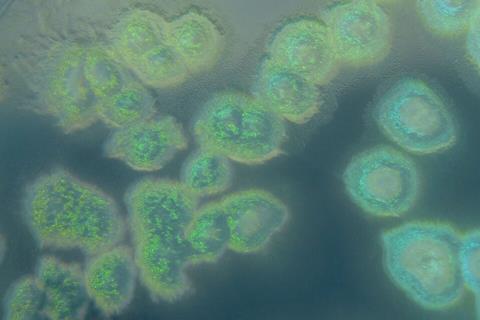

In this method, researchers engineer bacteriophages synthetically using sequence data rather than bacteriophage isolates. The team assembled a P. aeruginosa phage from 28 synthetic fragments, and programmed it with new behaviors through point mutations, DNA insertions and deletions. These modifications included swapping tail fiber genes to alter the bacterial host range and inserting fluorescent reporters to visualize infection in real time.

“Even in the best of cases, bacteriophage engineering has been extremely labor-intensive. Researchers spent entire careers developing processes to engineer specific model bacteriophages in host bacteria,” reflects Andy Sikkema, the paper’s co-first author and Research Scientist at NEB. “This synthetic method offers technological leaps in simplicity, safety and speed, paving the way for biological discoveries and therapeutic development.”

A new approach to bacteriophage engineering

With NEB’s Golden Gate Assembly platform, scientists can build an entire phage genome based on digital sequence data outside the cell, piece by piece, with any intended edits already included. The genome is assembled directly from synthetic DNA and introduced into a safe laboratory strain.

The method removes long-standing challenges of relying on the propagation of physical phage isolates and specialized strains of host bacteria, a heightened challenge for therapeutically-relevant phages, which specifically infect human pathogens. In addition, the process removes the need for labor‑intensive screening or iterative editing required by in-cell engineering methods.

Unlike DNA assembly methods that join fewer and longer DNA fragments, Golden Gate Assembly’s segments are shorter, making them less toxic to host cells, easier to prepare, and much less likely to contain errors. The method is also less sensitive to the repeats and extreme GC content found in many phage genomes.

Through simplification and increased versatility, the Golden Gate method of bacteriophage engineering dramatically shifts the window of possibilities for researchers dedicated to developing bacteriophages as therapeutic agents to overcome antibiotic resistance.

Molecular tools finding their purpose

Realizing the rapid method of synthetic bacteriophage engineering required an intersection of expertise between NEB’s scientists, who developed the basic tools to make Golden Gate reliable for large targets and many DNA fragments, and bacteriophage researchers at Yale University who recognized its potential, and reached out to collaborate on new, ambitious applications.

Researchers at NEB first worked to optimize the method in a model phage, Escherichia coli phage T7. Since then, partnering teams have worked with NEB scientists to expand the method to non-model bacteriophages that target highly antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

Synthesizing phages

A related study, which used the Golden Gate method to synthesize high-GC content Mycobacterium phages, was published in PNAS in November 2025 in conjunction with the Hatfull Lab at the University of Pittsburgh and Ansa Biotechnologies. Researchers from Cornell University have also worked with NEB to develop a method to synthetically engineer T7 bacteriophages as biosensors capable of detecting E. coli in drinking water, described in a December 2025 ACS study.

READ MORE: Phages with fully-synthetic DNA can be edited gene by gene

READ MORE: Researchers release phage images with unprecedented detail

“My lab builds ‘weird hammers’ and then looks for the right nails,” said Greg Lohman, Senior Principal Investigator at NEB and co-author on the study. “In this case, the phage therapy community told us, ’That’s exactly the hammer we’ve been waiting for.’”

Topics

- Andy Sikkema

- Ansa Biotechnologies

- Bacteria

- Bioengineering

- Cornell University

- Greg Lohman

- High-Complexity Golden Gate Assembly

- Infectious Disease

- Innovation News

- Microbial Genomics

- Microbiological Methods

- New England Biolabs

- One Health

- Phage Therapy

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Synthetic Biology

- University of Pittsburgh

- USA & Canada

- Viruses

- Yale University

No comments yet