A team of researchers at the University of Pittsburgh has developed a skin patch that can detect antibodies associated with COVID and flu infections. It’s orders of magnitude more sensitive than existing tests, uses just a half volt of electricity, and can return results in 10 minutes.

Their paper was published online this week. It will be the cover story on the upcoming print copy of the journal Analytical Chemistry.

READ MORE: Tiny chip speeds up antibody mapping for faster vaccine design

READ MORE: Researchers evaluate the safety and efficacy of a smallpox vaccine for preventing mpox

Alexander Star, professor of chemistry in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, has also developed sensors using a similar platform to detect, among other substances, marijuana and fentanyl.

An antibody test can indicate whether a vaccine has successfully taught someone’s immune system to fight a specific virus. If a test indicates soemone has mounted a strong enough response without a vaccine, they may not need to get a booster.

How it works

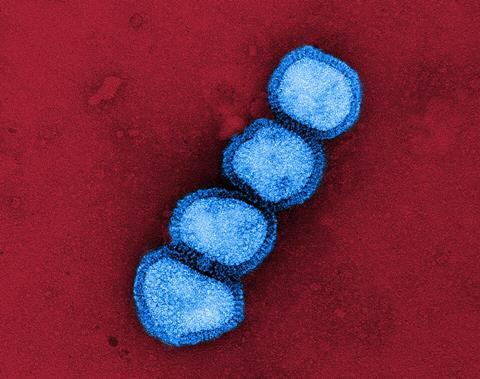

The sensor uses a virus-specific antigen attached to a carbon nanotube, which is 100,000 times smaller than a human hair. The sensor can be attached painlessly on the skin using a microneedle array which samples the fluids between skin cells. When an antibody binds to its partner antigen, the electrical properties of the nanotubes change, indicating their presence.

“It doesn’t penetrate too deep and so it’s not painful,” Star said. “It’s not touching any nerves and you’re not losing any blood, but you are getting the same results.”

Beyond ’SARS-Cov-2 and H1N1, this platform could be configured to identify any antibodies, including perhaps those associated with autoimmune diseases in which flareups are often triggered by otherwise harmless viral infections.

No comments yet